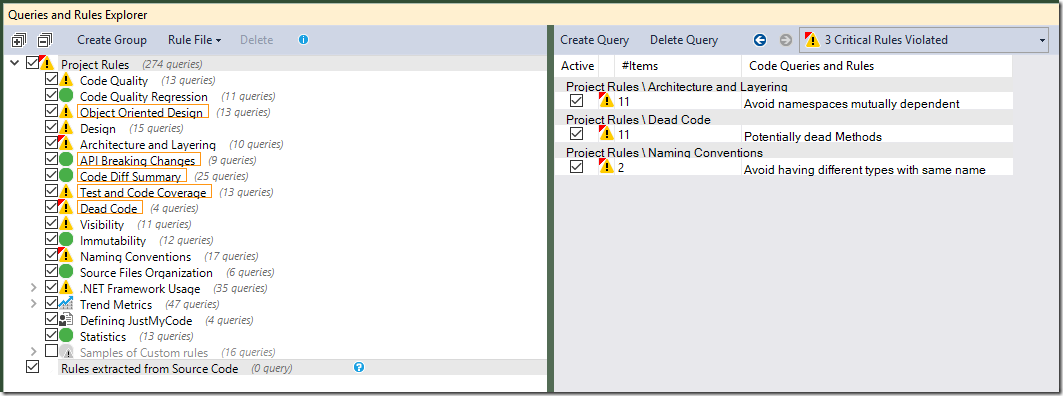

Following on from my look at the non-critical errors NDepend 6 found on my project, let’s look at the more serious stuff - the critical errors. Our old friend the Queries and Rules explorer shows me this:

So - mutually dependent namespaces, uncalled methods, and types with the same name as other types. Taking these in reverse order:

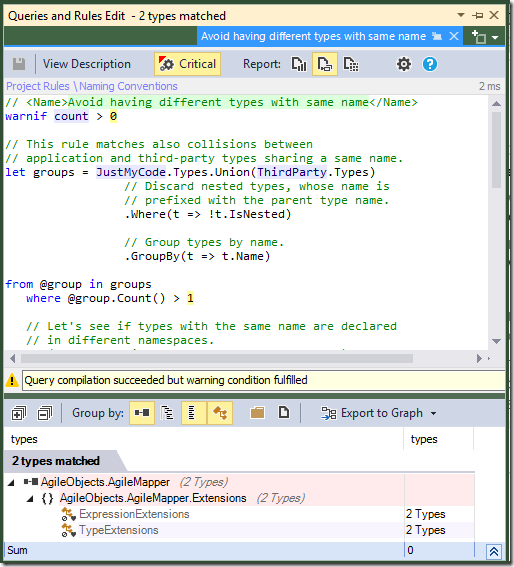

…the third rule has matched ExpressionExtensions and TypeExtensions. As an aside, it’s

worth mentioning how elegant the rule definition language is and how easily you can express complex

rules. Look at that! It’s great!

As you might expect, ExpressionExtensions and TypeExtensions contain extension methods for

Types and Expressions respectively. I only have one class of each name, so where’s the conflict?

Clicking ‘2 Types’ tells me:

It’s conflicted with another project of mine on which the mapper depends - ReadableExpressions - which creates a friendly view of an expression tree. So how big a problem is that?

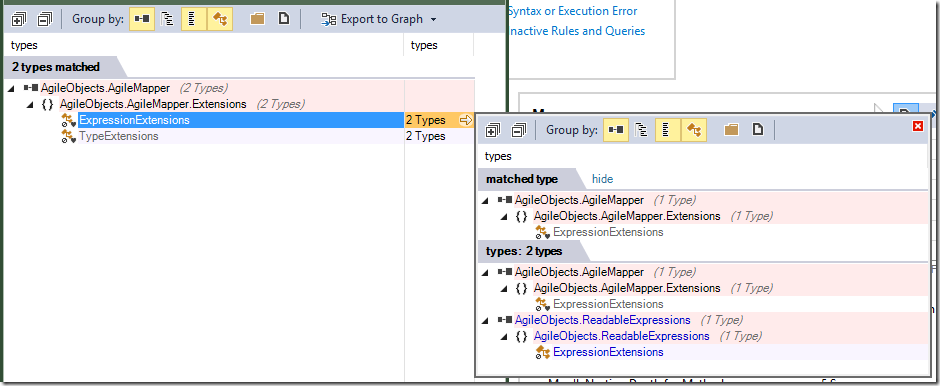

Naming things is hard, and following naming conventions is almost always a good idea. If I’d made a

class named StringBuilder this rule would apply, but I’d say these are a special case. You don’t

even use extension method classes directly - you import the namespace and use the methods - so it’s

not going to conflict with anything. With that in mind, let’s update the rule:

Look how easy that was!

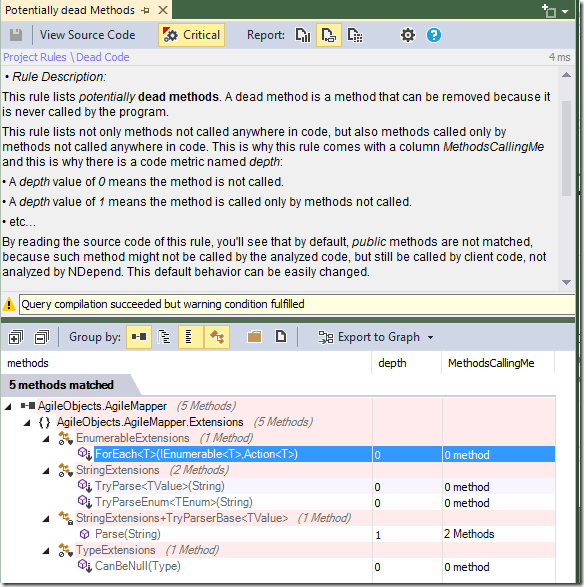

Moving on to the dead methods:

I’ve got the rule description view selected this time instead of the query - this is a new version 6 feature and is again typical of how helpful the tool tries to be :)

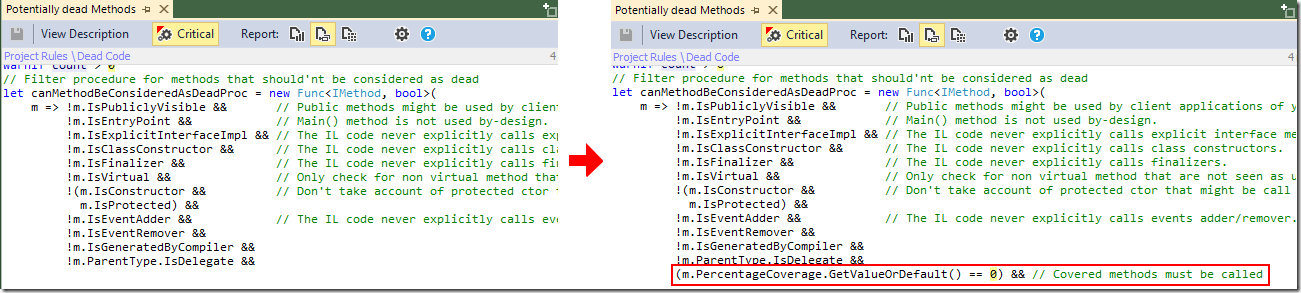

The first 4 of these methods are called, via reflection - the fifth one I copied from an earlier incarnation of the project and will be called in the future. As I mentioned before, finding methods which are called via reflection is going to be a very awkward task, but… hang on, we’ve got test coverage data! So if we update the rule:

We can easily exclude anything which has coverage. Using GetValueOrDefault() in the query also

keeps it relevant if there’s no coverage data available.

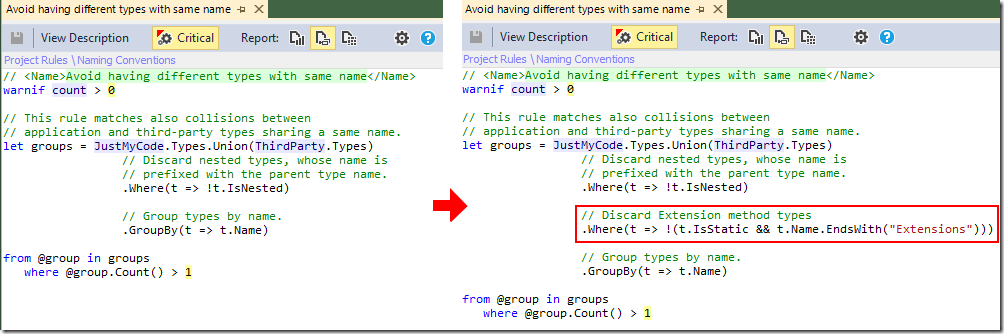

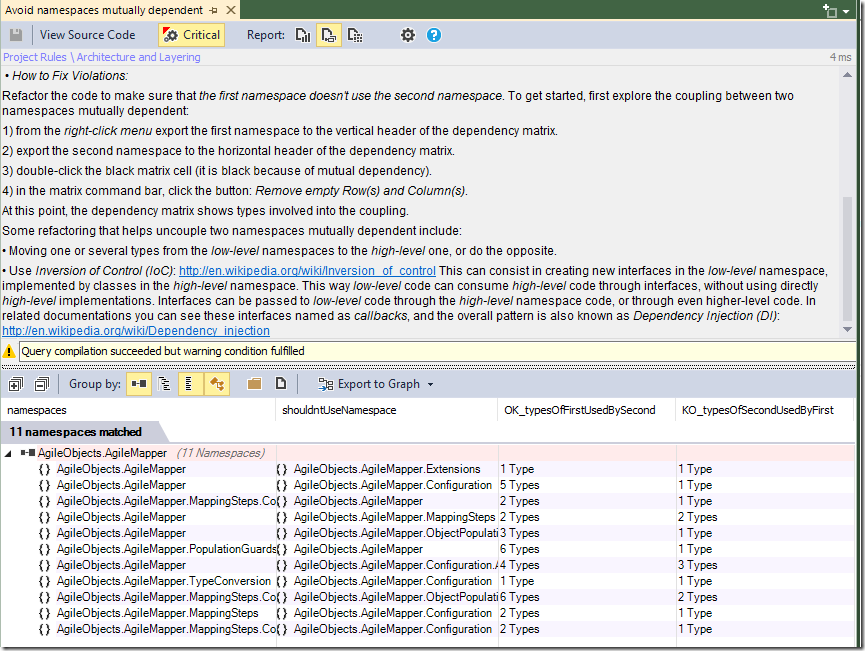

So finally - those mutually-dependent namespaces again. Here’s the details:

You can see that all but one of the violations is for the AgileMapper or

AgileMapper.Configuration namespaces. Most of the links to the former are to a Constants

class and to the latter a class exposing user-configured settings. This type of coupling can be

solved by inversion of control (as detailed in the rule description in the image above) - should I

do that here?

Constants is a static class with all constant or static readonly members. It’s a pure convenience

class enabling (for example) Constants.PublicStatic to be used in place of

BindingFlags.Public | BindingFlags.Static all over the place. In theory, I could create an

interface in (for example) AgileMapper.Extensions, and implement it in a class in AgileMapper,

passing an instance to the AgileMapper.Extensions namespace to break the coupling. The

configuration class is used everywhere as user-configured settings apply to lots of scenarios. In

theory, I could create an interface in (for example) AgileMapper.TypeConversion, and have

MappingConfiguration implement it, breaking the coupling. At this point I want to revisit my two

questions regarding rule violations:

-

Do I agree with the rule?

-

Is the cost of fixing it worth the improvement?

I certainly agree with the rule in many scenarios - abstracting some types of components is vital to

testable code. Are these examples worth fixing? I don’t think so. In order to abstract the

configuration class, each currently-coupled namespace will need its own interface - this would

leave MappingConfiguration implementing 5 interfaces just to break the coupling. Am I ever

likely to want to move MappingConfiguration into a different assembly or replace it with an

entirely new implementation? No, and the same is true of Constants. I remember seeing a long time

ago discussion about

how far to go with abstraction and decoupling, and I think these would be steps too far. So do I

want to switch the rule off? No. I think it’s an important one to keep an eye on, but like so many

of these rules, you have to apply common sense.

Which brings us to the end of my look at NDepend. Ultimately it’s a fantastically useful tool delivering insight and information, which can’t be a bad thing. Run it on your own project(s) and see what you find!

Comments

One comment