My current pet project is a chess-type board game using Node, Angular and TypeScript. This is my first time working with Node or Angular and the differences in the way they approach Dependency Injection - along with a recent blog by Cellfish - led to this post.

Defining DI

First, a refresher on what Dependency Injection is. Any non-trivial, non-throwaway application is split into components, each of which handles part of an overall task. There are various ways a component can access the other components it needs:

-

Static references: the component makes calls to static methods on static components.

-

Bastard Injection: (hey - I didn’t name it) the component itself creates instances of other components.

-

Service Location: the component uses a ‘service locator’ object to obtain instances of other components.

-

Dependency Injection: the component has the components it needs wired into it… in some way

I’ve come across the first setup more than once (usually accompanied by an AnemicDomainModel) and because everything’s hard-wired together, it’s difficult to test. Frameworks exist which let you interrupt and re-route static method calls (through IL-rewriting black magic), but that’s really just nice-to-know in case you find yourself with no other option. It looks like this:

public static class FooServices

{

public static void DoSomething()

{

BarOperations.HelpMeDoSomething();

}

}

public static class BarOperations

{

public static void HelpMeDoSomething()

{

// ...

}

}

…and it’s not Dependency Injection. The second setup comes with the option of doing proper DI, for example:

public class FooService

{

private readonly BarOperations _bar;

public FooService()

: this(new BarOperations())

{

}

public FooService(BarOperations bar)

{

_bar = bar;

}

public void DoSomething()

{

_bar.HelpMeDoSomething();

}

}

FooService here gets its instance of BarOperations through Bastard Injection - you can side-step injecting

it through the constructor via the parameterless constructor, which creates a new instance all by itself. This

may seem convenient, but it’s just as hard-wired as the first example, which gives you all the same problems.

Hence the slight and subtle pejorative in the name :) This is not Dependency Injection.

The third setup has a bad rep, but I think there’s an example of it which isn’t as bad. It looks like this:

public class FooService

{

private readonly BarOperations _bar;

public FooService()

{

_bar = ServiceLocator.Resolve<BarOperations>();

}

}

public class LaLaLaHelper

{

private readonly BarOperations _bar;

public LaLaLaHelper(IServiceLocator serviceLocator)

{

_bar = serviceLocator.Resolve<BarOperations>();

}

}

public interface IServiceLocator

{

T Resolve();

}

public static class ServiceLocator

{

public static T Resolve()

{

// Resolve from a wrapped DI container

}

}

So. FooService here is using a service locator as in the frowned-upon Service Locator Pattern - it has a

static reference to a service location class which it asks for its BarOperations instance. The problem with

this is that the relationship between FooService and BarOperations is hidden - there’s no way for clients

of the FooService class (other classes / people writing code against it / people writing tests against it)

to know that it depends on BarOperations and to therefore know they need to deal with that dependency up-front;

that’s why Service Locator is considered an anti-pattern.

LaLaLaHelper is also using a Service Locator, but I don’t think in quite such an unhelpful way. It declares

via its constructor that it requires an IServiceLocator implementation in order to do its job - that is, it

requires the ability to arbitrarily obtain instances of any class it chooses as and when it needs them. There

are examples of this in proper grown-up code like MVC’s

IDependencyResolver

- it is a Service Locator and it’s not great that

LaLaLaHelperdoesn’t tell you what it’ll be ‘locating’, but it’s as good as service location gets and it is Dependency Injection. It’s just injection of the widest-ranging, most general purpose, least informative dependency imaginable.

And so finally onto Dependency Injection done properly:

public class FooService

{

private readonly BarOperations _bar;

public FooService(BarOperations bar)

{

_bar = bar;

}

}

…there. FooService uses its constructor to declare its dependencies, and we can create a BarOperations

instance however we choose and hand it over. This is Dependency Injection.

DI in Angular

And so to DI in Angular. The following TypeScript declares a controller object and registers it with Angular:

class GameController {

constructor(

windowService,

gameFactory: IGameFactory,

scope: IGameScope) {

// ...

}

}

angular

.module(gameApp)

.controller(

"GameController",

["$window", $gameFactory, "$scope", GameController]);

The module method retrieves my game’s Angular module using its name, and the controller method registers the

controller. controller’s array argument specifies the dependencies by name, with the final item in the array

being the controller object’s constructor function. While we are using

magic strings to reference the dependencies, the controller object

gets to declare its dependencies in its constructor and Angular wires everything together - this is Dependency

Injection, why is why it gives you that a warm, fuzzy feeling.

DI in Node

Node uses Asynchronous Module Definition (no it doesn’t! See the comments), which you use by calling a require function to obtain your dependencies. Hopefully the following example is self-explanatory:

import path = require("path");

import http = require("http");

class NodeApp {

constructor() {

var publicRoot = path.join(__dirname, "public");

var app = this._createApp(publicRoot);

var server = http.createServer(app);

Let’s review the types of DI we’ve got here:

-

The

pathandhttpobjects are obtained using therequirefunction - this is textbook Service Location. Ohhhhh yes it is. -

The

pathandhttpobjects are statically referenced within theNodeAppconstructor. -

__dirnameis set by the Node environment and is local to each module. This is also statically referenced and as far as I can tell is essentially injected by Node outside of your control.

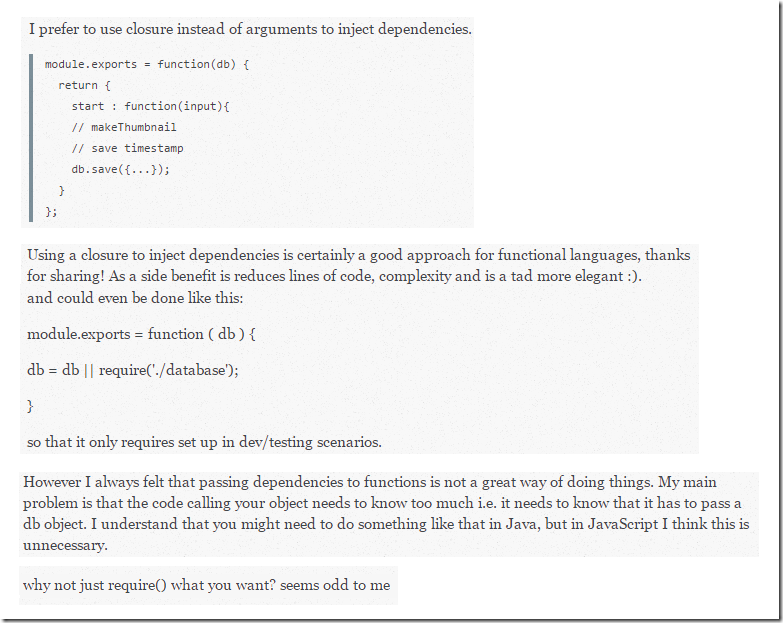

This is an abbreviation of some code from the Node entry-point class for my game, but I hope sometime soon it won’t look like this. It… isn’t pretty. It’s not Dependency Injection. I’ve found some discussion about Node’s DI approach, and there were some interesting comments:

…the first comment is advocating what is essentially constructor injection as an alternative to the parameter

injection originally set out in the blog - that’s warm and fuzzy, I agree with and like that. The second comment

advocates Bastard Injection “so that it only requires set up in dev/test”, but I’ve only ever seen problems

result from having setup differ between environments, so I’m not sure of the benefit. The third comment advocates

different practices between Java and JavaScript, but I’d say these principles -

inversion of control and discoverable dependencies - are

language-agnostic, so I don’t follow the logic. The fourth comment (originally made on a blog about

DI in Angular)

questions what’s wrong with just using require like Node does as standard - the answer is service location and

hidden dependencies.

It seems odd to me that this is Node’s standard way of dealing with dependencies - especially in light of the way it’s done in Angular - but there’s what looks like a good Node DI package available so I’m going to give that a go. Fingers crossed I’ll be able to make my server-side JavaScript as composable as the client-side stuff. If not… I’ll just cry or something, I dunno.

Comments

2 comments